Girmityas: The Forgotten Story of Indian Indentured Laborers

The history of slavery is a dark and painful chapter in the annals of humanity, one that has left indelible marks on societies across the globe. While the transatlantic slave trade is well-documented and widely discussed, there exists a lesser-known but equally significant narrative – the Indian indenture system. This system emerged in the wake of the abolition of slavery in various European colonies in the 19th century, serving as a substitute for forced labor. Over the course of several decades, more than 1.6 million workers from India were transported to toil in distant lands, leaving an enduring legacy that still influences the demographics and cultures of regions far from their homeland.

The Indian indenture system, established in response to the changing global dynamics and the decline of traditional chattel slavery, offers a unique lens through which to examine the complexities of labor exploitation, migration, and the formation of diasporic communities. This article delves into the multifaceted aspects of this system, tracing its historical origins, its impact on the Indian diaspora, and its connection to the broader context of slavery and labor exploitation worldwide.

As we embark on this journey through history, we will uncover the stories of those who endured the hardships of indenture, exploring the diverse destinations to which they were transported, including the Caribbean, Natal, East Africa, Réunion, Mauritius, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Fiji. We will also delve into the enduring legacies of these migrations, which have given rise to Indo-Caribbean, Indo-African, Indo-Fijian, Indo-Malaysian, and Indo-Singaporean populations, each with its unique cultural tapestry woven from the threads of their shared past.

In recounting this lesser-known chapter of human history, we aim to shed light on the complexities of slavery and labor exploitation in India, as well as the far-reaching consequences of the Indian indenture system. It is a story of resilience, endurance, and the indomitable human spirit that transcends borders and generations, leaving an indelible mark on the tapestry of global history.

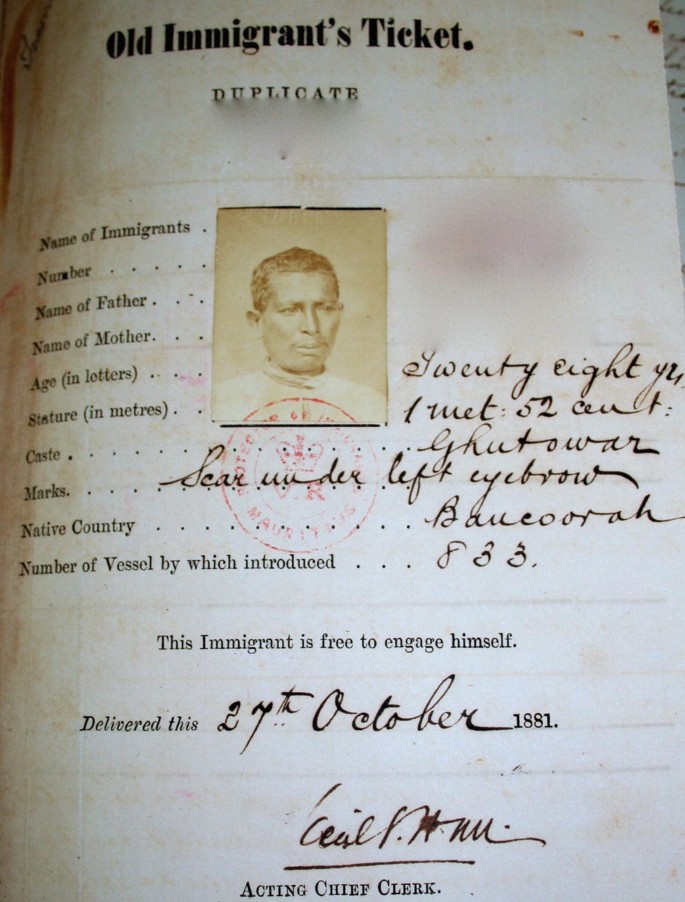

|

| Indentured labours at Reunion |

The 19th century marked a significant period in the history of Indian labor migration, driven by the colonial aspirations of European powers and the economic interests of sugar planters in their overseas territories. The French Indian Ocean island of Réunion, situated east of Madagascar, provides one of the earliest examples of the systematic introduction of Indian laborers under this new arrangement. On January 18, 1826, the Réunion government laid down the terms for this endeavor, a document known as "girmit." According to girmit, Indian laborers were required to make a voluntary declaration before a magistrate, agreeing to a contractual period of five years of labor in the colonies. In return, they were promised a monthly wage of 8 rupees, equivalent to approximately $4 in 1826, along with provisions. These laborers were primarily sourced from Pondicherry and Karaikal, regions in India.

The French experiment on Réunion was an early indication of the burgeoning Indian indenture system, but it was not without its challenges. The first attempt to import Indian laborers to Mauritius in 1829 met with failure. However, by 1838, approximately 25,000 Indian laborers had been successfully shipped to Mauritius, setting the stage for the wider expansion of the indenture system.

In parallel with the aspirations of the sugar planters, the East India Company's Regulations of 1837 outlined specific conditions governing the dispatch of Indian laborers from Calcutta. These regulations required emigrants and their agents to appear before designated government officers with a written contract outlining the terms of their employment. The initial period of service was fixed at five years, renewable for further five-year terms, and at the end of their service, laborers were to be repatriated to their port of departure. Strict standards were set for the vessels used for emigration, including provisions for space, diet, and the presence of a medical officer. In 1837, these regulations were extended to Madras, further expanding the scope of the indenture system.

However, as news of this new system of labor migration spread, it sparked a campaign akin to the anti-slavery movement in both Britain and British India. Concerns arose over the exploitation and abuses faced by indentured laborers under these contracts. To address these issues, a committee was appointed on August 1, 1838, to investigate the export of Indian labor. This committee uncovered reports of maltreatment and exploitation within the system, prompting action. On May 29, 1839, the British government took the step of prohibiting overseas manual labor, imposing a penalty of 200 Rupees or three months in jail for anyone attempting such emigration.

|

| Regvister of a ship carrying indentured labours |

Despite the ban on Indian labor export, a limited number of laborers continued to be sent to Mauritius via Pondicherry, a French enclave in South India. However, the prohibition was eventually lifted in 1842 for Mauritius and in 1845 for the West Indies, marking a resumption of Indian labor migration.

Yet, these suspensions in Indian immigration were not isolated incidents. For instance, between 1848 and 1851, Indian immigration to British Guiana was halted due to economic and political unrest resulting from the Sugar Duties Act of 1846.

These early developments set the stage for the complex and often troubled history of the Indian indenture system, which continued to evolve throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the subsequent sections of this blog, we will explore the lived experiences of indentured laborers, the conditions they faced, and the enduring legacies of this system in various parts of the world.

The Indian indenture system, born out of the aspirations of European planters and the British government, was not without its complexities and challenges. The ban on Indian labor export had initially been put in place as a response to the concerns raised by the anti-slavery committee, but it faced relentless pressure from planters eager to secure a reliable workforce. Under mounting influence from European planters and their supporters, the British Government finally relented on December 2, 1842, permitting emigration from major Indian ports like Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras to Mauritius. This decision was a pivotal moment in the expansion of the indenture system.

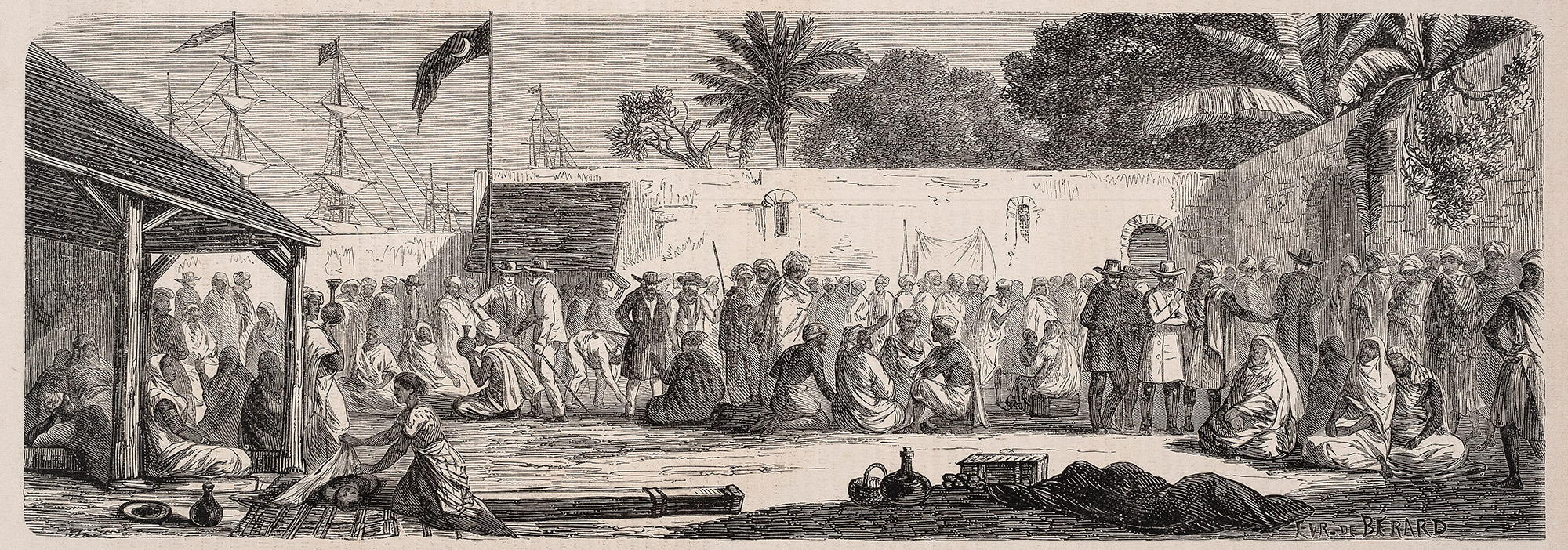

|

| Ticket of an indentured labour |

Emigration agents were appointed at each departure point to oversee the process, and penalties were imposed for abuses within the system. Laborers were guaranteed return passage to their homeland after a minimum service of five years, and this privilege could be claimed at any time thereafter. With the lifting of the ban, the first ship set sail from Calcutta to Mauritius on January 23, 1843. The influx of immigrants was so substantial that it caused a backlog in processing, prompting the Protector of the Immigrants in Mauritius to request additional support.

In 1843 alone, a total of 30,218 male and 4,307 female indentured immigrants arrived in Mauritius, signifying the rapid pace of this migration. The first ship from Madras reached Mauritius on April 21, 1843, further diversifying the origins of the labor force.

Despite efforts to regulate the system, the existing regulations failed to completely eradicate abuses. Recruitment through false pretenses continued, leading the Government of Bengal to restrict emigration from Calcutta. Departure from Calcutta was now permitted only after laborers signed a certificate from the emigration agent, countersigned by the Protector of Immigrants. Nevertheless, migration to Mauritius persisted, with 9,709 male unskilled laborers (known as Dhangars) and 1,840 female family members transported in 1844.

|

| Grimityas on their return voyage |

Repatriation of laborers who had completed their indenture remained problematic, with a high death rate during the return voyages. Investigations revealed that regulations governing these return voyages were not consistently followed.

As the demand for labor in Mauritius continued to outstrip the supply from Calcutta, permission was granted in 1847 to resume emigration from Madras, and the first ship set sail from Madras to Mauritius in 1850.

Plantation owners sought to extend labor contracts beyond the initial five-year period. To persuade laborers to stay on, the Mauritius Government offered a gratuity of £2 to each laborer who chose to remain in Mauritius and forgo their claim to a free passage back to India. Furthermore, the government aimed to discontinue the provision of a return passage, leading to a change in conditions. On August 3, 1852, the Government of British India agreed to new terms where unclaimed passages would be forfeited after six months, with safeguards for the sick and poor.

Another significant change in 1852 allowed laborers to return after five years, provided they contributed $35 toward the return passage. After a decade of service, they would qualify for a free return passage. However, this change had unintended consequences, as few were willing to commit to a ten-year indenture period, and the $35 contribution proved prohibitive. Consequently, this change was discontinued after 1858.

Recognizing the importance of family life in retaining laborers, efforts were made to increase the proportion of women among the indentured immigrants. Early migration to Mauritius had a small proportion of women, but on March 18, 1856, the Secretary for the Colonies issued a dispatch requiring that women comprise 25 percent of the total immigrants for the 1856–7 season, with subsequent years seeing a cap on the number of males dispatched to not exceed three times the number of females. These policies aimed to encourage family life within the colonies.

Trinidad took a distinct approach by offering laborers incentives to settle in the colony once their indentures had expired. Beginning in 1851, a £10 payment was offered to those who forfeited their return passages. This was later replaced with land grants, and in 1873, further incentives were provided, including 5 acres of land and £5 in cash. Trinidad also implemented an ordinance in 1870 that prohibited new immigrants from being assigned to plantations with a death rate exceeding 7 percent.

|

| Grimityas at banana plantation |

The success of the Indian indenture system in providing a ready labor force, albeit at a significant human cost, did not go unnoticed by other European plantation owners and colonial authorities. As European powers sought to meet the demands of their burgeoning colonies, they began to establish agents in India to recruit Indian laborers.

For instance, French sugar colonies, such as Réunion, recognized the potential of the indentured labor system and commenced recruitment via French ports in India without the knowledge of British authorities. By 1856, Réunion alone was estimated to have accommodated approximately 37,694 laborers. However, it wasn't until July 25, 1860, that France received official permission from British authorities to recruit labor for Réunion, at an annual rate of 6,000. This permission was later extended on July 1, 1861, granting France the right to import "free" laborers into its colonies, including Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French Guiana (Cayenne). Notably, indenture contracts in the French colonies had a longer term of five years compared to British colonies, return passages were provided at the end of the indenture (not after ten years as in the British colonies), and the Governor-General had the authority to suspend emigration if any abuses were detected.

Danish plantation owners also ventured into the recruitment of Indian laborers for St. Croix. However, this indenture system proved to be short-lived.

|

| Grimityas at Reunion |

In 1864, permission was granted for emigration to Queensland, Australia, but no Indians were transported under the indenture system to this part of Australia.

The indentured labor system evolved over time, and there were significant discrepancies in its implementation across different colonies. In 1864, colonial British government regulations attempted to standardize recruitment practices for Indian labor to minimize abuse of the system. These regulations included:

Requiring recruits to appear before a magistrate in the district of recruitment, not just at the port of embarkation.

Licensing of recruiters and imposing penalties for not adhering to recruitment rules.

Defining the roles and responsibilities of the Protector of Emigrants.

Establishing rules for depots.

Changing payment for agents from commission to salary.

Setting uniform standards, including the proportion of females to males at 25 females to 100 males.

Despite these efforts, sugar colonies often enacted labor laws that disadvantaged indentured laborers. For example, in Demerara, an ordinance in 1864 made it a crime for laborers to be absent from work, misbehave, or fail to complete five tasks each week. In Mauritius, new labor laws in 1867 restricted time-expired laborers from escaping the estate economy, requiring them to carry passes displaying their occupation and district. Anyone found outside their district without employment risked arrest and deportation to an Immigration Depot, effectively restricting their movement and freedom.

Indian labor transportation extended to Suriname under an Imperial agreement. In exchange for Dutch rights to recruit Indian laborers, the Dutch transferred old forts in West Africa to the British and relinquished British claims in Sumatra. Laborers were signed up for five-year contracts and provided with a return passage at the end of their term, subject to Dutch law. The first ship carrying Indian indentured laborers arrived in Suriname in June 1873, followed by six more ships that same year.

Between 1842 and 1870, a total of 525,482 Indians emigrated to both British and French colonies. The majority, 351,401, went to Mauritius, while others were distributed among Demerara, Trinidad, Jamaica, Natal, Réunion, and other French colonies. This figure does not include those who went to Mauritius earlier, those who went to Ceylon or Malaya, and those recruited illegally in the French colonies. By 1870, the indenture system had firmly established itself as a method for providing labor to European colonial plantations.

| An indenture agreement |

The indenture agreement of 1912 laid out the terms and conditions governing Indian labor migration to various colonies. These agreements were instrumental in regulating the labor force and the relationships between the laborers and their employers:

- Period of Service: Laborers were contracted to work for a period of five years from the date of their arrival in the colony.

- Nature of Labor: Laborers were primarily engaged in agricultural work related to the cultivation of the soil or the manufacture of produce on plantations.

- Working Days and Hours: Laborers were required to work every day, except Sundays and authorized holidays. They worked nine hours on each of five consecutive days in a week, commencing with Monday, and five hours on Saturdays.

- Wages: When employed at time-work, adult male laborers above the age of fifteen received not less than one shilling per working day (equivalent to twelve annas), while adult female laborers of the same age received not less than nine pence (equivalent to nine annas) per working day. Children below the age of fifteen received wages proportionate to the amount of work done. Task or ticca-work rates were also defined based on the performance of specific tasks.

- Return Passage: Emigrants were allowed to return to India at their own expense after completing five years of industrial residence in the colony. After ten years of continuous residence, with at least five years of industrial residence, they were entitled to a free return passage if claimed within the specified time frame. Children born within the colony were entitled to a free return passage until a certain age.

- Rations and Accommodation: Laborers received rations from their employers during the first six months after arrival, as prescribed by the government. Suitable dwellings were assigned to them free of rent and were maintained by the employers.

- Healthcare: Laborers received free medical care, hospital accommodation, medicines, and medical comforts when ill.

- Marriage: Laborers with existing spouses were not allowed to marry another spouse in the colony unless their previous marriage had been legally dissolved. However, if they were married to multiple spouses in their home country, all spouses could accompany them to the colony and be legally registered.

The indenture system allowed for the employment of laborers on plantations while providing them with basic necessities and legal protection. However, it's important to note that despite these regulations, many laborers still faced difficult and challenging conditions.

|

| Gopal Krishna Gokhale |

The Indian indenture system saw significant changes over time, and it ultimately faced pressure for reform and abolition. Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a moderate Congress leader, played a pivotal role in ending the export of indentured labor to Natal (present-day South Africa) in 1911. The British-led Indian indenture system for other colonies eventually ended in 1917. This decision was driven by multiple factors, including pressure from Indian nationalists and declining profitability, rather than solely humanitarian concerns.

The impact of the indenture system on various colonies was significant, leading to changes in demographics, culture, and literature. It left a lasting legacy that continues to shape the identity and heritage of Indo-Caribbean communities and other regions influenced by this historical migration.

|

The indenture system resulted in significant demographic changes in several countries:

- In Mauritius, Mauritians of Indian origin make up 65.00% of the population.

- In Guyana, Indo-Guyanese constitute 39.83% of the population.

- In Trinidad and Tobago, Indo-Trinidadians and Tobagonians account for 35.43% of the population.

- In Suriname, Indo-Surinamese represent 27.40% of the population.

- In Fiji, Indo-Fijians make up 37.50% of the population.

These Indo-Caribbean and Indo-Pacific communities have had a profound impact on the culture, literature, and social fabric of their respective countries. Notable Indo-Caribbean writers, such as V.S. Naipaul, have contributed significantly to the literary heritage of the region. This migration history and the resulting cultural diversity continue to shape the identities and narratives of these nations.

Indentured labor, a nefarious system imposed by colonial powers, stands as a haunting reminder of the exploitation and plunder that India endured during its harrowing colonial era. This oppressive system emerged in the 19th century, cunningly supplanting chattel slavery, as it served the insatiable economic interests of European colonizers who callously refused to relinquish their grip on the relentless pursuit of cheap labor after the abolition of slavery. At the epicenter of this ruthless machinery was the British Empire, whose iron-fisted rule led to the forceful migration of over 1.6 million Indian laborers to far-flung lands, leaving an indelible and agonizing scar on the Indian subcontinent.

|

| Year Wise Data |

This system was nothing short of calculated plunder – a stark theft of India's most valuable resource: its people. It not only robbed the nation of its human capital but also systematically stripped away the dignity of countless individuals who were treated as mere commodities for the economic gain of their colonial overlords. The impact of this orchestrated exploitation was cataclysmic, leaving an indomitable mark on India's collective psyche. It drained the nation of its vigor and vitality, leaving behind an impoverished and fractured populace burdened by the weight of exploitation.

Data paints a heart-rending picture of the sheer magnitude of this tragedy. Millions of Indians, drawn from their homes under false pretenses and promises of a better life, were transported across vast oceans to toil in brutal conditions on foreign soil. Families were torn apart, and communities were uprooted, creating a void that still resonates in India's social fabric. These indentured laborers endured back-breaking labor, grueling working hours, and deplorable living conditions, all while being subjected to the cruelty of overseers who showed little regard for their humanity.

|

| Place Wise Data |

The economic implications were staggering. India's human resources, the lifeblood of its progress and prosperity, were siphoned away to fuel the economic engines of distant colonial powers. The wealth generated from the labor of these indentured workers enriched the coffers of the colonizers, perpetuating their dominance over India. The economic disparity created by this systematic exploitation lingers to this day, with India grappling with the legacy of lost opportunities, unequal development, and persistent poverty in regions from which laborers were forcibly extracted.

Yet, the impact of the indentured labor system transcends mere economic statistics. It wrought cultural disintegration as families were scattered across continents, languages and traditions were suppressed, and the bonds that held communities together were severed. The trauma inflicted on those who endured the brutality of indenture echoed through generations, leaving a legacy of pain and hardship.

The indentured labor system was a stark testament to the rapacious greed of colonial powers, a symbol of their unrelenting pursuit of wealth and power at the expense of the colonized nation's welfare. It was an exploitation so deeply entrenched that it became woven into the fabric of India's history, shaping its destiny and casting a long shadow that still envelops the nation today. This dark chapter in India's past is a stark reminder of the inhumane consequences of colonialism, a chapter that calls upon us to remember the suffering of those who were victimized and to strive for a future where such exploitation is never repeated.

The story of Indian indenture is a complex chapter in the history of global migration, colonialism, and labor exploitation. From the early 19th century to the early 20th century, more than 1.6 million Indian laborers embarked on journeys that would shape the destiny of multiple nations and leave an enduring imprint on their cultures.

|

| Caste Wise Data |

The indenture system, born in the wake of the abolition of slavery, aimed to provide a readily available labor force to colonial powers in need of workers for their plantations and industries. It promised laborers passage to distant lands, shelter, wages, and certain rights, yet the reality often fell short of these promises. Many laborers faced harsh conditions, long working hours, and limited freedoms, as well as a separation from their homeland and families.

This system not only transformed the economies of the receiving colonies but also brought about profound demographic changes. Indo-Caribbean, Indo-African, Indo-Fijian, Indo-Malaysian, and Indo-Singaporean communities emerged, leaving a rich cultural legacy. Writers like V.S. Naipaul, among others, have added their voices to the literary heritage of these regions, providing insights into the experiences of their ancestors.

As the indenture system expanded beyond British colonies to French, Dutch, and Danish territories, it became clear that it was not solely driven by humanitarian concerns but also by economic interests. The system evolved over time, responding to various challenges and pressures, but it ultimately faced calls for abolition. Gopal Krishna Gokhale's efforts and the changing economic landscape led to the gradual dismantling of the indenture system.

Today, the legacy of Indian indenture lives on in the vibrant cultures and diverse societies of the nations shaped by this migration. It is a testament to the resilience and contributions of those who endured the hardships of indenture. Their stories remind us of the complexity of history and the need for empathy and understanding when reflecting on the past.

In recognizing the enduring impact of the Indian indenture system, we pay tribute to the laborers who left their homeland, faced adversity, and helped build the societies we know today. Their journeys, struggles, and triumphs continue to enrich our collective narrative and underscore the importance of acknowledging the multifaceted history that has shaped our world.

Bibliography

- Burman, B.K. Roy. "The Other Indians: Essays on Pastoralists and Prehistoric Tribal People." Primus Books, 2012.

- Giuliano, Maurizio, and Elvira Graner, editors. "From the Colonial to the Contemporary: Images, Iconography, Memories, and Performances of Indian Girmityas." Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

- Bahadur, Gaiutra. "Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture." The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

- Crawford, Amanda S. "Indentured: Behind the Scenes at Guantanamo." University of California Press, 2016.

- Turner, Mary. "From Chattel Slaves to Wage Slaves: The Dynamics of Labour Bargaining in the Americas." University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Look Lai, Walton. "Indentured Labour, Caribbean Sugar: Chinese and Indian Migrants to the British West Indies, 1838-1918." Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

- Gillion, K. L. "Girmitiyas: The Origins of the Fiji Indians." Oxford University Press, 1962.

- Rajan, Gurukkal. "The Road to Fiji: Immigrant Dreams, Migrant Lives." University of Hawaii Press, 2007.

Comments

Post a Comment